Internal Parasites in Gouldians

& Other Finches

Kristen Reeves, Meadowlark Farms Avian Supply, Inc.

Before I go on to explain some of these potential problems, I must reiterate the importance of good husbandry and maintaining a preventive maintenance schedule for your birds. Many of the below issues can be avoided if cage, food & watering devices are kept clean (not sterile – clean), and the birds are proactively treated to prevent internal parasites. If you are unsure of your ability to determine the overall health and wellness of your birds, please take them to an Avian Veterinarian for diagnosis before medicating!

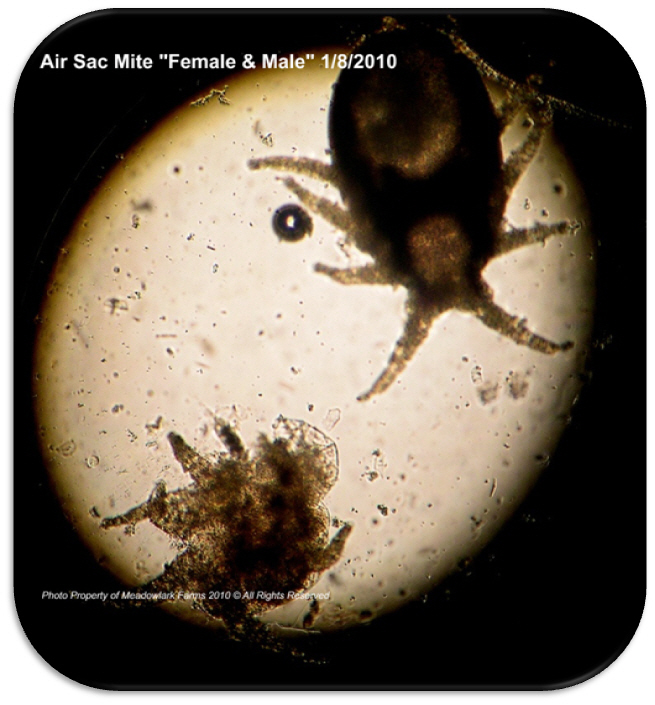

AIR SAC MITES

Air sac mites are tiny internal parasites that invade the air sacs and trachea of the bird. It is thought they are dormant in almost all Gouldians and remain so until the immune system is lowered. They feed on the vascular parts of the respiratory system when they are active. They are opportunistic and typically only surface when the bird’s immune system is compromised. Poor nutrition, poor husbandry, weak genes, and stress can all contribute to a weak immune system.

In addition to causing respiratory issues and anemia, an infestation can lower the immune system further allowing other issues to arise. Once out of dormancy and actively feeding, anemia can cause weakness in the bird. A heavy burden of mites may then cause the symptoms we most often hear of. Because they will reside dormant in the posterior air sacs of dormant birds until their immune system is lowered, it is preferable to be proactive in their treatment. In severe cases, air sac mites will clog the airway making it difficult for the bird to breathe. An infected bird may breathe with an open beak, and may make a telltale “clicking” or gurgling sound, much like it is continuously cracking seed. It may have a frothy discharge around its beak and nostrils.

Birds with air sac mites may also “tail bob”. When treated pro-actively, air sac mites are not usually a problem. However, if your bird shows signs of an infestation and this parasite is not eliminated early, treatment can actually kill your bird. As the insecticide works, it kills large numbers of mites that can totally block the airway.

S76 (Ivermectin) can be used to treat large flocks where handling each and every birds is difficult. Scatt (Moxidectin in an oil-based, topical treatment form), is applied topically on the skin – whether it be under a wing, on the skin of the thigh, or between the shoulder blades; the important part being that it makes contact with the skin and is not applied on the feathers. Water soluble Moxidectin may be added to the drinking water if you can find it.

S76 is offered 2 consecutive days per week for 3 weeks. It only remains in the bird’s system for 24 hours making consistency KEY. Ivermectin, the active ingredient in S76, remains stable in the water for up to 6 hours and should be mixed and replaced fresh each time you offer it.

If you are comfortable handling your birds or only have a few, a single drop of Scatt (about the size of a pea) should eliminate the mites in a single dose as long as the burden isn’t heavy and the issue was caught early. Scatt stays in the bird’s system for 3 weeks (21 days), and should not be administered more often than that. In most cases, a single dose will eliminate the mites, but occasionally a second does in 21 days will be required.

Air sac mites are spread through sneezing, wiping of beak on perch, and through feeding of the chicks by the parents. They are rarely found in the droppings unless a bird happened to eat one of them.

NOTE:Not all symptoms of air sac mites are actually caused by air sac mites! The symptoms may often be confused with bacterial infections, respiratory infections, or even obesity. Be sure to check with your Veterinarian before making any treatment decisions!

PROTOZOAL INFECTIONS

WORD OF CAUTION: It has been my experience that bleach and hot water do not necessarily kill protozoa, eggs, or oocysts shed when your bird eliminates. Keeping cage grates, perches & papers clean will help to keep your birds from picking at droppings in the cage.

Protozoal infections are spread through infected bird droppings, occasionally backwash in watering devices, and/or when parents are feeding chicks. It is my humble opinion that protozoa may well be another issue that remains dormant in a bird’s system until the immune system is lowered. They can’t just materialize out of the blue, so unless there was another parasite acting as host, or it was spread by another bird, it makes sense that they are sometimes dormant in some species.

Most common types of Protozoal infections:

- Trichomonas may cause lesions in the beak, throat and crop that appear cheesy, yellow, or white. These lesions can create mucus that clogs the airway and causes breathing difficulties. They are most easily found in crop wash results and have “signs” under the scope that indicate their presence even if the actual organism isn’t seen specifically. I’m not sure how to explain these “signs”, but they are always present whether the actual swimmers are present or not. In my experience, Trichomonas is rarely seen in the droppings. Once under the scope, they are rather large and easy to see. Once a bird is infected, it is often a carrier even after treatment though may never show signs of infection again in the future.

- Giardia embeds in the intestines, preventing absorption of nutrients. It often causes severe diarrhea or enteritis-like symptoms in the birds. Droppings usually start out “lumpy” then quickly turn wet and messy with very little form to the fecal matter. Urine and urates will spread far and wide around the fecal portion, and may dry looking very white in a large ring surrounding the fecal matter.

- Cochlosoma is often the biggest culprit in Society finches. They multiply quickly and float freely in the intestines, preventing absorption of nutrients, though not as damaging to Societies as to other species. Droppings are often “lumpy” and wetter than normal. Once established, there may be enough in a single sample to cover an entire slide.

Symptoms of protozoa infections can include tail bobbing, sitting fluffed, green droppings, yellow droppings, and grey droppings coated in a sleeve of urates. Undigested seed is often seen in the droppings. “Going light” and vomiting are often symptoms. An infected bird will often drink huge amounts of water, making the droppings wetter than normal.

Most protozoal infections I’ve scoped tend to come from “lumpy” droppings that are not well-formed, and are usually coated in urates (the white portion of the dropping). However, there are also those lovely poops we breeders refer to as “popcorn poop”. The droppings look just like a popped corn kernel. Sometimes droppings can look completely normal – mostly from carrier birds - so if you suspect your bird has a protozoal infection but cannot perform tests yourself to confirm, it is important to have fecal smear diagnostics performed by a professional.

Protozoal infections can cause many types of problems in your birds. If left untreated, they may cause liver and kidney damage, poor condition, lack of appetite, and death. Mutation birds are often more susceptible due to weaker genes. Society finches are notorious carriers. If you use Societies to foster or keep them in the same cage with your Gouldians or other susceptible species, it is important to treat your entire flock during a preventive maintenance routine. If you use them as fosters, I recommend treating them with Ronivet 12% 1 week before eggs are due to hatch, then again 1 week after the eggs hatch. Ronidasole is perfectly safe for use with even brand new chicks.

Ronivet 12%, Ronivet-S, and Ronex (Ronidasole) is the only readily available treatment for the average bird keeper.

Click here to see videos of protozoa under the microscope on our YouTube Channel.

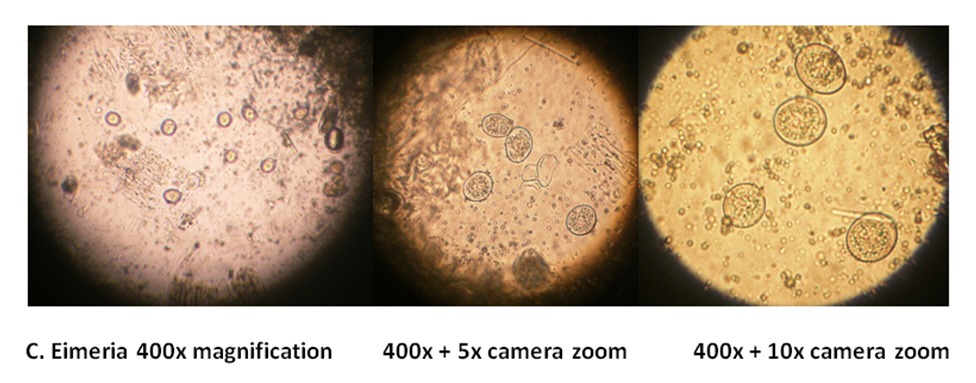

COCCIDIA

Coccidia is actually considered a protozoan, though isn’t motile so we tend to think of it differently. And while coccidia used to be something rarely seen in captive pet birds, it is now becoming more prominent requiring active treatment. It has yet to rear its ugly head in MY aviary, but I have begun to see more and more in my client’s birds and other aviaries.

It seems that most birds harbor a few coccidia in their systems. It is my humble opinion that as long as it does not get out of control, this is completely normal and doesn't usually affect the health of the bird. If it is just a few, I merely lower the pH of the water and monitor the bird. If it is more than one or two, I will treat.

Because coccidia is another opportunistic bug, it usually only becomes a problem when the bird’s immune system is compromised. Regularly seen during times of high heat and humidity, it is often accompanied by Candida. In most cases, the bird will produce “creamy” urates and droppings, and the vent may become soiled or stained. Birds may sit huddled with their head tucked, or sit in the food dish perpetually, as if they are starving. Weight loss, poor condition, and tail bobbing may also be seen.

Coccidiosis infections may be controlled but not cured with coccidiostats. If I see an infection worthy of treatment (more than 1 or 2 organisms per sample), I will first lower the pH of the water using Dr. Rob Marshall’s MegaMix to see if the bird can fight it on its own. If not, treatment then begins with Trimethoprim/Sulfa for a full 7 days. Baycox, which is no longer readily available, was once the best cure for coccidia. Enrofloxin is now usually prescribed by Veterinarians, though he/she may have newer choices to stop and prevent coccidiosis - always ask before treating!

^^Above C. Eimeria at 400x magnification with 5x camera zoom

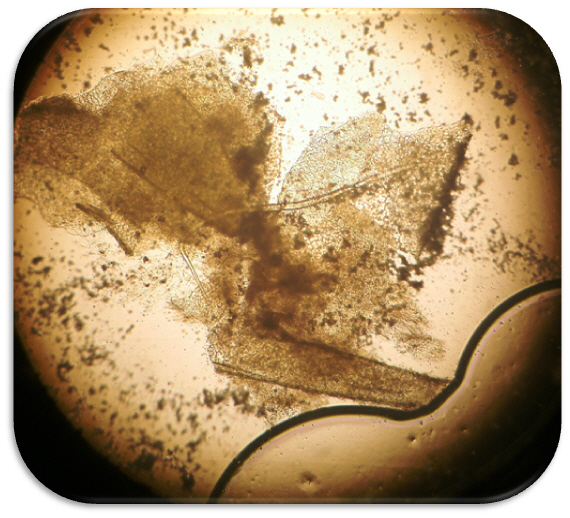

WORMS

There are several types of worms your birds may become infested with depending on their environment. The following are those most commonly found in captive or pet birds I've tested:

- Tapeworms

- Round worms

- Gizzard worms

Worms are not generally found in finches that do not eat live insects or are housed in indoor cages or aviaries unless an infected bird has been introduced. BUT - I have experienced roundworms in my birds and my client's birds when they've eaten seed that has had insect hosts in it. After talking a friend through a necropsy and finding the bird to be riddled with worms, I HIGHLY recommend you worm your birds at LEAST quarterly, regardless of whether you “think” they have worms or not.

Worms require an intermediary host such as fleas, ants, house flies, flour moths, pantry beetles, or any of their young. These hosts may carry worm eggs. Once ingested, the eggs within that eaten host hatch and infect the bird. Unfortunately, most Veterinarians I’ve run into do not believe birds get worms. Unless they are an Avian specialist (and even if they are!), they may never see samples with worms or eggs in them. Most worms I’ve seen in captive INDOOR birds have been roundworm species acquired via host insects in the seed.

Because of the high metabolism of finches and other small birds, pathogens are not always passed in every sample. It is very important your Vet check at least 3 samples per day (preferably from morning, noon, and night) over the course of three days (for a total of 9 samples) to be relatively certain your birds do not harbor worms. Some worms physically attach themselves to the lining of the alimentary canal (some only in the intestines, others from beak to vent), while others merely float around in the alimentary canal blocking nutrient absorption and causing the bird’s immune system to lower. This causes a myriad of symptoms including, diarrhea, black stringy poop, fluffing, “going light”, poor feather quality, breeding issues, and anemia - though there are many other potential symptoms of worms.

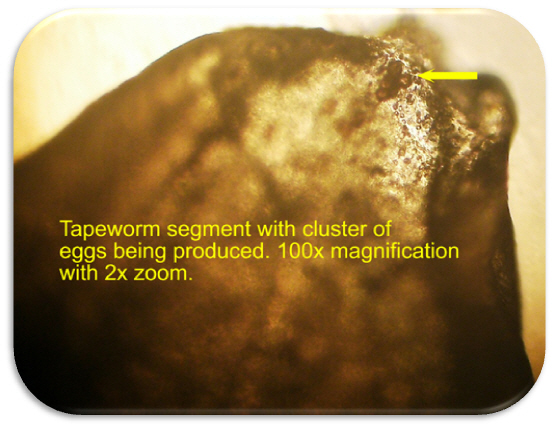

Tapeworms are usually only found in birds from OUTDOOR aviaries or on dirt floors where rodents, insects, or other pests can deposit eggs and/or be the host.

In the case of tapeworms, you may find “pieces” or “segments” of the worms in the bird's droppings or hanging from the vent, but you probably won't know that your bird has worms without checking the droppings for eggs under a microscope. In my experience, tapeworms are a rare occurrence in finches.

However, roundworms and their many subspecies are more often seen and are not typically visible to the naked eye in a dropping sample. Eggs typically hatch in 7-10 days, so follow up treatments are advisable.

Seed that has been infested with insects can also be a source of worms. No bugs in your seed you say? Guess again! It doesn't matter how clean you think your seed is or where you get it - all seed has the potential to carry insect hosts making it extremely important to run your birds through a preventive maintenance program at least quarterly. It is important to pro-actively treat for worms unless you are able to run your own fecal exams or take your birds to an Avian Veterinarian regularly.

Worm eggs are NOT affected by worming medication, heat, bleach or severe cold. The outer shell of the worm egg is extremely hard and protects the contents from these treatments. The only way to rid the birds of worms is to treat pro-actively, then follow up in 7 days from the first day of treatment to prevent any worms that may have hatched after the first treatment from procreating and continuing the cycle.

NOTE: After years of crushing seed to find the hosts, I have found that insect content in the seed is typically driven by the weather where the seed was grown. I have found more evidence of insects and noticed more worm infestations in the birds when the growing season had been very dry. Keep in mind that most seed has been grown two seasons or more ago and is then stored for packaging - you may not be able to know for sure how long the seed has been stored. But the important thing to remember is that many insects burrow into the seed while it is developing - much like a Mexican Jumping Bean - and stay inside the seed until it is eaten or the fully formed insect emerges! While not all seed is infected, it is always wise to have droppings checked by a professional at least once per year to detect a potential infestation! When adding new birds to your flock, it is advisable to always run them through a quarantine procedure that includes de-worming.

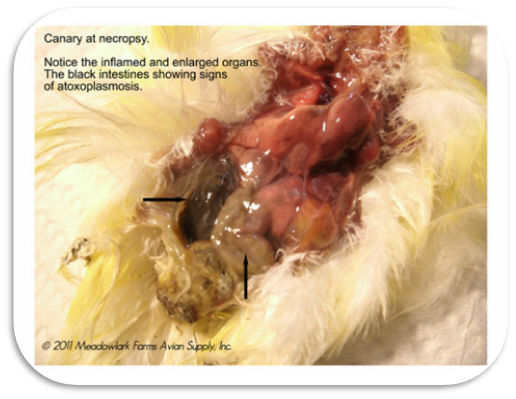

ATOXOPLASMOSIS

“Atoxoplasmosis is a parasitic disease primarily of passerine birds, especially Canaries [and} Finches... It is caused by species of the coccidian protozoan Atoxoplasma, a host-specific parasite. Atoxoplasma serini, the species found in canaries, is not infectious to Gouldians; likewise, the species infecting Gouldians is non-infectious to [Canaries]... The parasite is transmitted via the fecal-oral route and not by mites as was formerly thought when it was known as Lankesterella. Parasitism may cause rapid and fatal disease in fledgling birds...”

Please see entire journal article, “An Overview of Atoxoplasmosis in Birds”; by K. Leigh Sheridan, DVM and Kenneth S. Latimer, DVM, PhD http://www.vet.uga.edu/vpp/clerk/Sheridan/index.php

FINAL WORD...

The information contained here is for reference purposes only. As always, if you suspect your bird is sick, take it to an Avian Veterinarian!